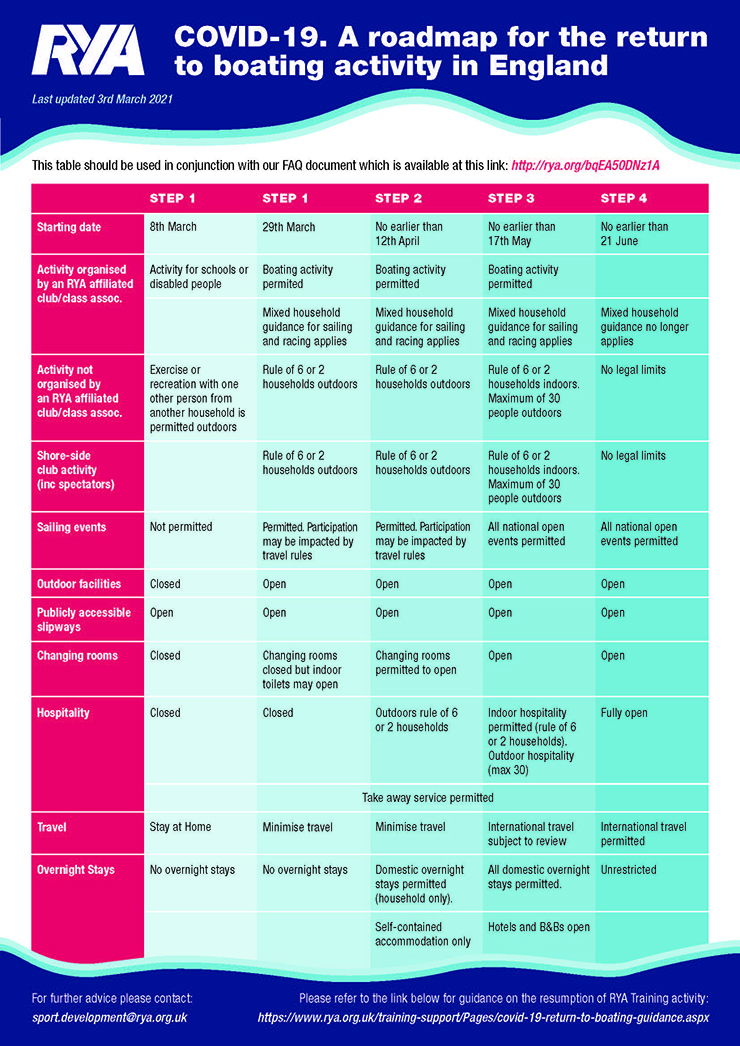

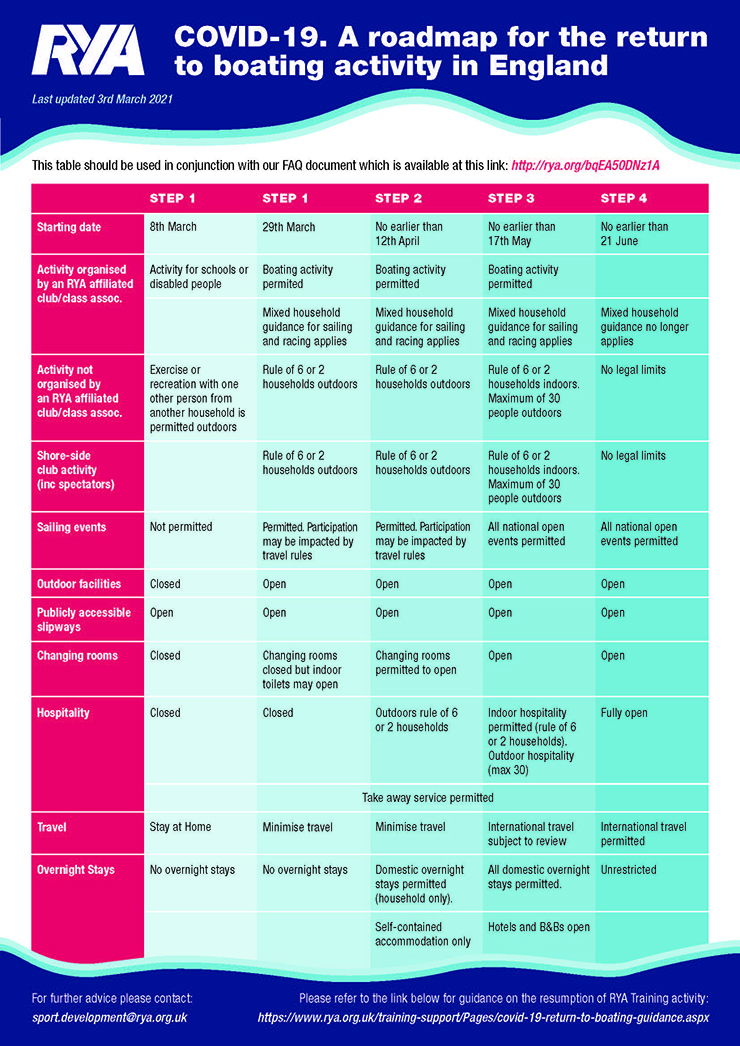

The RYA has created a very useful table of what is allowed and when:

For more information please refer to the RYA Website

The web site for eastern Solent boat fishing

The RYA has created a very useful table of what is allowed and when:

For more information please refer to the RYA Website

I recently came across this interesting little video showing the inside of the Nab Tower, I’m not sure how they were allowed access! Enjoy.

The Southsea Coastal Scheme has now started and will be of interest to anyone passing on or by the seafront whether on land or sea. The existing sea defences which prevent Portsmouth from flooding are now very old and need to be brought up to date. There has been extensive planning of this work to ensure it enhances the visitor experience as well as protecting the island. It will eventually provide improved beach access but the work, costing over £100 million will inevitably cause some disruption.

There is an excellent and very informative website here – have a look at the 3D visualisations on the map too. There will be large barges, dredgers and cranes moving close to the shore, and I expect there will be a lot of sediment distubed in the construction process which may affect fishing. Best advice is: proceed with caution in the area and it’s probably best to avoid the immediate area for fishing if there are boat movements visible.

My father Peter Merritt passed away on 30th November and I wanted to share some memories here that relate to fishing and boats.

Dad was always fascinated by boats small and large. He was brought up in East Ham and would often visit the London docks to see which steamers had arrived. Soon after he married Mum in 1953, they bought a wooden sailing dinghy which they renovated – Mum remembers trying to sandpaper over a growing bump that was me (to be). When I was of pushchair age they went sailing in Helford River with me strapped to the floorboards and were caught in a squall. This scared them so the boat was sold. Probably just as well, safety equipment wasn’t much of a thing then.

When I was about seven years old Dad bought me a fishing rod from Woolworths. It had a plastic reel/handle and a metal rod so it was more of a toy really, but it functioned and Dad bought a pack of size 16 hooks to nylon. With the business end sorted the rest didn’t matter. We went to a local stream, baited up with garden worms and to my surprise I actually caught a fish. OK it was only a minnow but he lived on for many years in our fishtank. That was the start of it and all these years later I’m still hooked on fishing.

As a boy I was reliant on being taken to fishing spots, and Mum would be persuaded to take me, a picnic, my fishing rod (I had a better one by now) and a pile of socks that needed darning, down to the Chelmer and Blackwater Canal. Dad travelled on business quite a lot but in school holidays he would research fishing spots near his business visits. He would drop me off to fish, then after his call he would come and collect me and we would drive home. I fished random places all over East Anglia.

We lived well inland in Essex so sea fishing was limited to family holidays or the occasional trip to Southend Pier. In 1972 we spent a fortnight in Ilfracombe and I pleaded with Dad to take me out on a charter trip. We caught mackerel, dogfish, bream, conger and Dad caught a very large ray of some sort. He was so delighted it didn’t take much to get another trip in before the holiday ended.

One thing led to another and somehow a plan for our own boat took shape. We toyed with the idea of fitting out a Colvic hull (they were built locally), but in the event Dad bought a 23 foot wooden Norwegian fishing boat called Punsj which we spent the summer converting into a motor/sailer. We moored it off Heybridge on the Blackwater, and spent many happy days pottering around the coast at six knots. No VHF radio, and our most sophisticated electronics was a Seafarer LED echo sounder! If we got stuck on the mud (which we did) we had to stay there until the next tide.

In 1978 my parents moved to Derbyshire, I graduated and moved to Hampshire and Punsj was sold. Dad never bought another boat but was always keenly interested in mine – starting with a 14 foot dinghy, then a Shetland Alaska in which we all followed the Tall Ships Regatta in Weymouth Bay. After owning my Trophy for 19 years I bought Rebel Runner and Dad was so keen to see it he was determined to get on board even though he was in his late 80s. I have happy memories of he and I sitting in the cabin yarning about past boating experiences, eating slightly burnt sausage rolls and beans.

My favourite memory is of the two of us in Punsj tied up in Bradwell marina on a sunny day. We must have been waiting for Mum and my brother Jonathan or something, who were taking their time to arrive. I remember Dad, usually always busy, leaning back in the sun and saying “Isn’t this marvellous. There’s is absolutely nothing I ought to be doing.”

Miss you Dad, and thank you for everything.

This wreck is a popular angling mark where in summer many boats stop to feather for mackerel. It is easily located by the north and south cardinal buoys marking the wreck and shows as a distinctive hump on the fishfinder screen.

You may also know the wreck as the Flag Theofano MV, a freighter built in 1970. She was 324 feet long, weighing 2,818 tons She had several names in her 20 years of service before sinking in January 1990. But why did she sink? Why was her loss not discovered sooner? What happened to most of the crew? The circumstances of the wreck remain a mystery.*

On the 29th January, Flag Theofano was carrying 4,000 tons of bulk cement from Le Havre to Southampton, with a crew of 19. That night a severe storm drove many ships to find shelter making it very difficult for the marine traffic controllers to find safe berths for them all. They were unable to provide a berth for Flag Theofano so she was called on the radio and instructed to anchor off Bembridge in the area called St Helens Roads, where many commercial vessels can be seen anchoring today. This was acknowledged by Captain Ioannis Pittas and the marine traffic controller then continued to look after other vessels in the area.

The next morning, Flag Theofano was called on the radio with new berthing instructions but there was no reply. Other vessels nearby were called but they could not see the vessel. She had disappeared. The full horror of the situation was revealed when an empty lifeboat and two bodies – the Captain and Second Officer – were found on West Wittering beach. Flag Theofano had sunk, nobody had heard a distress signal and nobody had seen it happen. At the time they didn’t even know where the wreck was located.

Boats searching the area came across an oily patch in the water, bubbles escaping and ropes attached to something below the surface. As soon as the weather eased, divers were sent down and found the wreck upside down on the seabed 20 metres below the surface right by the main shipping lane leading to the Solent. Three other bodies were washed up on the shore several weeks later: the Radio Officer, Bosun and Ibrahim Hussain.

Salvage operations started in August 1990 but by now the cargo of cement had come into contact with the water and fully hardened, creating a huge block of concrete that was impossible to move, either to locate any bodies or to salvage the wreck. The bodies of the 14 remaining crew were never found. They may still be under the wreck, or they may have been swept away in the storm.

Nor do we know why the ship sank. It must have been sudden or distress signals would have been sent. Possibly the cargo shifted in the storm leading to a capsize, but was this before she anchored, or did she drift from the anchorage to Dean Tail later in the night? We will never know. It seems bizarre in this age of total electronic surveillance that even in 1990 a ship a few miles from land can simply disappear and not be missed for hours.

The only human connection we have to this wreck is the unmarked grave of one of the sailors in Portsmouth’s Kingston Cemetery: Ibrahim Hussain who was only 19 years old. If you pass the wreck at Dean Tail, spare a thought for him and his 18 colleagues (all from Chios Island in Greece) who have been forgotten by history and are just a distant memory to their families.

* Update September 2022: the grave of Ibrahim Hussain has now been marked with a headstone. Although we can never know for certain what happened that night, Martin Woodward, the professional diver who investigated the wreck, has written a book in which he has a very plausible explanation about what actually happened. However, having solved that mystery, other mysteries remain! You can read more about the wreck here:

If you would like to know what the wreck looks like close up, this video on YouTube gives a rather murky view. The wreck is lying on a seabed of mainly mud covered in a layer of shells.

I made a lot of friends and connections on World Sea Fishing when it was run by Mike Thrussell. After it was taken over (and in my opinion declined), Mike lay low for a bit but now he is back with a new Sea Fishing Forum. Pop over, sign up and join in!

Do you ever fancy a toasted sandwich, pannini or stuffie on board but you only have a one-burner stove and a kettle? Here is a way of bringing joy to a cold fishing day. Firstly, make your pannini, sandwich or stuffie (stuffed bap or roll) using heatable ingredients and preferably with cheese to bind it all together. Ham, bacon, cooked mushrooms, cheese, tomato, onion, cooked chicken, pesto, cooked meatballs/leftover burgers, sundried tomatoes are all ingredients you can experiment with. Now individually wrap the pannini/sandwich/stuffie tightly in strong aluminium foil. Go fishing. When hunger strikes, fire up your gas ring and take out a dry fring pan. Place your foil parcels in the pan and put on the heat. Turn them every two minutes for six to eight minutes. Heat gently or you could end up setting them on fire. If your turning and heat application are right, when you open the parcel you will find a hot pannini oozing with melted filling. If not, wrap it up again and take another couple of turns. The secret is to heat low and slow enough that it melts through to the centre, and hot enough that the top and bottom are crispy.

Steve Andrews came across this old gem by a Captain S. Norton-Bracy (you could discover new continents with a name like that). He kindly allowed me to scan it so you could take a trip back in time. Not all was good in those days – gaffing shark and conger for example. Milbro rods too, remember them? Tunny (tuna) of immense size were caught from Scarborough. Will they return? Enjoy a trip back to 1963 with this scanned copy.

Many of us were planning to use our boats this Spring, then suddenly we were prevented from getting to them even to shut them down properly. You may be worried that the prolonged idleness has harmed the engine, or you could cause harm by starting it without any further checks.

This week I attended an excellent webinar from Premier Marinas where Jonathan Parker of Parker Marine Services described what to do to minimise any engine damage when starting for the first time after lockdown. Here’s what he shared.

I won’t go into detail on the usual daily pre-start checks, obviously you would do these anyway:

Pay particular attention to the raw water filter if fitted, because if your boat is in the water unused for a long period, marine creatures can climb into the filter and start living there.

The following are additional checks advised by Jonathan.

On a diesel engine you can do this by holding the Stop button or the decompression lever down while you crank the engine. This operates the oil pump and puts some oil in the bearings before loading them with a running engine.

Now you are ready to start the engine. Again, there are some standard checks you would always do after the engine starts:

Raise the speed to 1200rpm in neutral. This helps the impeller draw water in. Now for some extra checks.

On an outboard you can see a water tell-tale jet. With a raw water strainer fitted you can see the water flow. On an enclosed system like an outdrive, feel the impeller housing – it should feel distinctly colder than the surrounding engine as water flows through. The same with the exhaust elbow. If it is difficult to reach you can use an infrared thermometer.

Ensure the boat is tied up securely with extra spring lines to secure bollards.

Run the engine in gear for 30 minutes or at idle for 45 minutes to bring it up to working temperature.

If no problems are evident and you are allowed out, you can proceed. If you discover any problems, at least you are still at your berth and not drifting down the Langstone Run towards the pier (my personal nightmare).

If you are not allowed out, you need to shut the boat down as if you may be leaving it for some time.

Let’s hope we are allowed out soon and can get back to enjoying our boating. The guidelines above are useful for starting your engine or running up your engine for any prolonged period without use, whatever the reason. Anglers are used to having a boat tied up for weeks on end due to bad weather – this now gives us a good excuse to spend time on your boats even if you can’t go fishing!

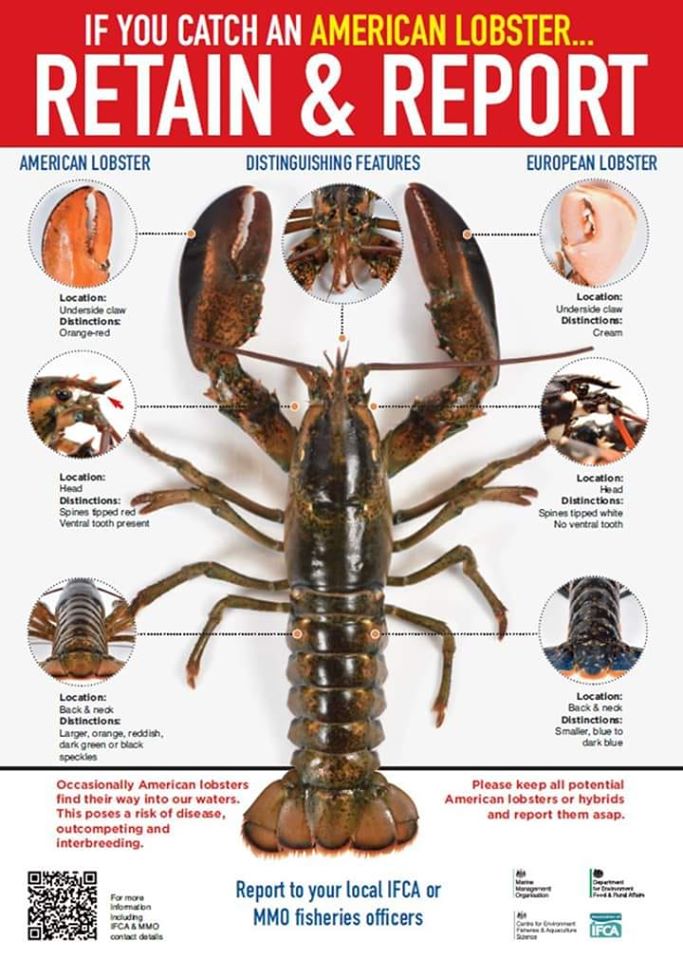

Cefas have launched a campaign to raise awareness of the threat to our lobsters from the non-native species of lobster, the American lobster. This Defra-funded initiative encourages fishers and others to “retain and report” any American lobsters that they capture, to measure and reduce impacts they are having in our marine environment.

(see identification chart below)

American lobsters have been imported to the UK since the late 1950s for consumption in restaurants and homes. American lobsters tend to grow to larger sizes than European lobster, have a larger dietary range, are more tolerant of different habitats, are more aggressive and produce more eggs than European lobsters. This means they are at a competitive advantage over the native species. American lobsters might also carry the bacterial disease, Gaffkaemia, or Epizootic Shell Disease. Transferring these diseases to native stocks could result in major economic losses to fishers. There is also a risk of American lobsters bringing other non-native species to our waters, such as barnacles and other small invertebrates which have attached themselves to the lobster.

The campaign aims to engage with lobster fishers explaining the legal position, how to identify an American lobster, the risks posed by the animals and the importance of retaining and reporting them to their local fisheries officers at the Inshore Fisheries and Conservation Authority (IFCA) or Marine Management Organisation (MMO). Knowingly releasing a non-native species to the wild is an offence under the Wildlife and Countryside Act, including returning one to the sea at point of capture.

The project lead at Cefas, Debbie Murphy, said “This a great opportunity for us to work with industry to gain information about whether these animals are affecting their fishery or not. By collecting this data Defra will be in a stronger position to make informed decisions regarding policy, and able to work to protect both the trade in American lobsters and wild stocks of European lobsters”.

Reports of American lobsters caught in our waters have historically been in low numbers and generally single animals, contributed to by escapes from holding tanks or releases by well-meaning members of the public or religious groups. The biggest contributor to American lobsters in English waters was a mass-release in June 2015 of 361 specimens off Brighton by Buddhist monks as part of their religious practice known as ‘fang sheng.’ In the months following this release, 136 American lobsters were removed from the sea in the surrounding area making up a large proportion of the 149 American lobsters reported from 2012 to 2018.

Almost 5 years on from the mass release and with less than half of the American lobsters having been reported as recaptured, Defra are keen to know what impact the animals may have had.

Posters and leaflets designed to help fishers understand the key features commonly associated with American lobster compared to European lobster, along with contact details to report suspected American lobsters have been produced by Cefas and are available on the GB Non-Native Species Secretariat website. Similar campaigns are planned in Scotland, Northern Ireland and Wales in 2020.

© 2026 Boat Angling

Theme by Anders Norén — Up ↑